How Artists See

Painters may view scenes in a way that's similar to how the world really is:

A mishmash of colors, lines and shapes.

Monitor on Psychology: February 2010 (A monthly magazine by the American Psychological Association)

By Sadie F. Dingfelder

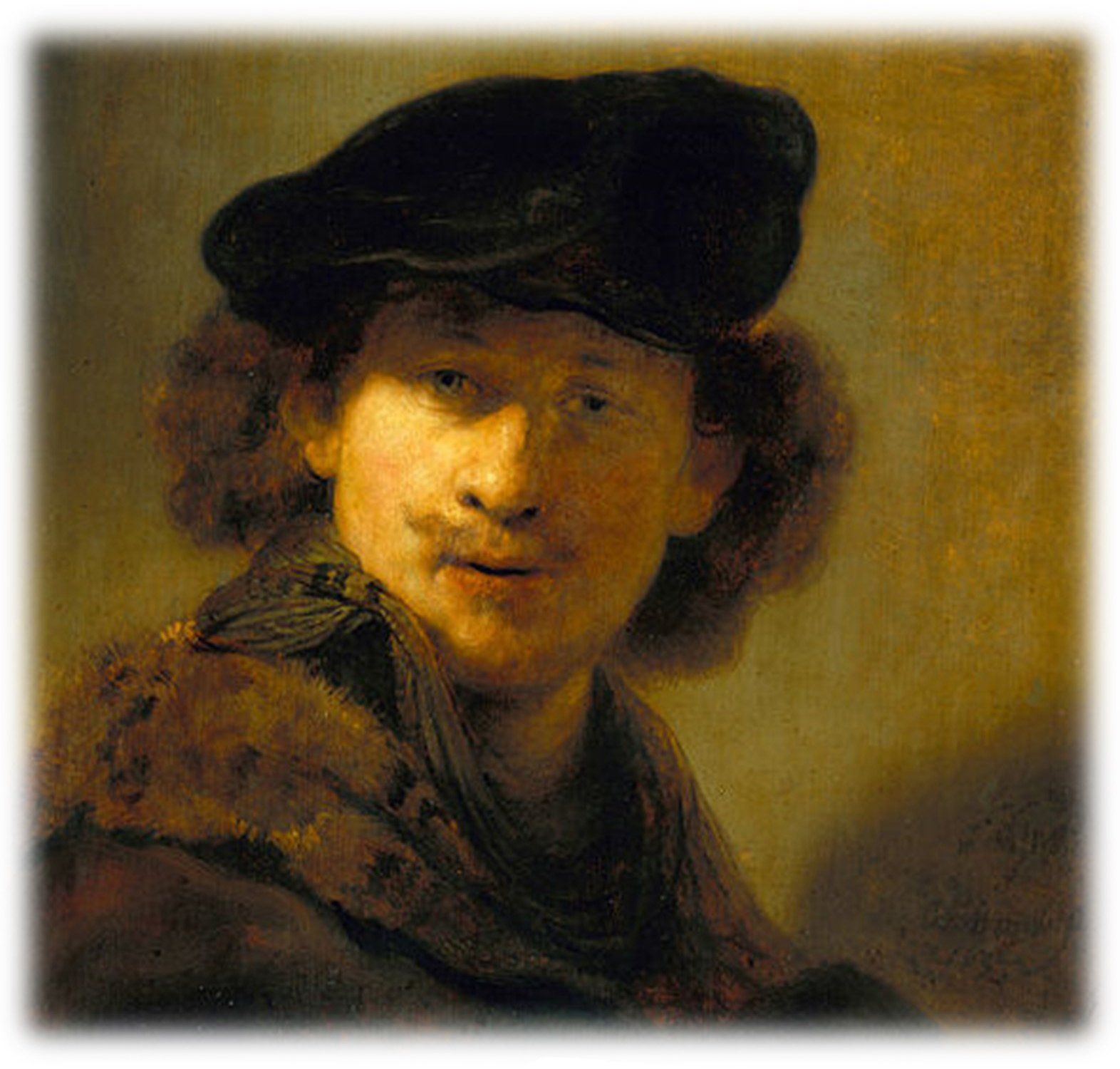

Rembrandt Self-portrait

Note: Underlining in article below by P. Kampas

Can you sketch a landscape, or even a convincing piece of fruit? If not, chances are that your brain is getting in the way, says painting teacher and landscape artist David Dunlop.

“People don’t see like a camera,” he says. “We go through life anticipating what we are going to see and miss things — which is why so many wedding invitations go out with the wrong date.”

In his art classes, one of the first things Dunlop tells students is to stop identifying objects and instead see scenes as collections of lines, shadows, shapes and contours. Almost instantly, students sketches look more realistic and three-dimensional.

Artists have long known there are two ways of seeing the world, says University of Oslo psychology professor Stine Vogt, PhD. Without learning to turn off the part of the brain that identifies objects, people can only draw icons of objects, rather than the objects themselves. When faced with a hat, for instance, most people sketch an archetypal side view of a hat, rather than the curves, colors and shadows that hit our retina.

In fact, artists’ special way of seeing translates into eye scan patterns that are markedly different from those of nonartists, according to a study by Vogt in Perception (Vol. 36, No. 1). In her study, she asked nine psychology students and nine art students to view a series of 16 pictures while a camera and computer monitored where their gazes fell. She found that artists’ eyes tended to scan the whole picture, including apparently empty expanses of ocean or sky, while the nonartists focused in on objects, especially people. Nonartists spent about 40 percent of the time looking at objects, while artists focused on them 20 percent of the time.

This finding suggests that while nonartists were busy turning images into concepts, artists were taking note of colors and contours, Vogt says.

While it takes years of training to learn to see the world like an artist, a common visual disability may give some people a leg up, says Bevil Conway, PhD, a neuroscience professor at Wellesley. In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2004, he and Harvard neurobiologist Margaret Stratford Livingstone, PhD, analyzed 36 Rembrandt self-portraits, and found that the artist depicted himself as wall-eyed, with one eye looking straight ahead and the other wandering outward.

This condition, called strabismus, affects 10 percent of the population and results in stereoblindness — an inability to use both eyes to construct an integrated view of the world. Stereoblind people can’t see “magic eye” images, in which a chaotic background turns into a single three-dimensional image. They also have limited depth perception and must rely on other clues, such as shadows and occlusion, to navigate the world.

Rembrandt’s stereoblindness, says Conway, may have given him an advantage in seeing the world like an artist. It’s no accident that art teachers often tell their students to close one eye before sketching a scene, he says. The eye’s imperfect optics, which form a slightly blurred image of any scene, also may be a factor, he adds.

“Rembrandt had a whole lifetime of honing the ability to render three-dimensional images in two-dimensional space,” he says.

Stereoblindness may also give lesser-known artists an advantage, Conway says. A yet-unpublished study by Conway and Livingstone finds that the art students are far more likely to have the visual disability than non-artists.

Vogt, a painter as well as a scientist, says that stereoblindness and concept-blindness help artists see the world as it really is, as a mass of shapes, colors and forms. As a result, artists can paint pictures that jar regular people out of our well-worn habits of seeing.

“People don’t see like a camera,” he says. “We go through life anticipating what we are going to see and miss things — which is why so many wedding invitations go out with the wrong date.”

In his art classes, one of the first things Dunlop tells students is to stop identifying objects and instead see scenes as collections of lines, shadows, shapes and contours. Almost instantly, students sketches look more realistic and three-dimensional.

Artists have long known there are two ways of seeing the world, says University of Oslo psychology professor Stine Vogt, PhD. Without learning to turn off the part of the brain that identifies objects, people can only draw icons of objects, rather than the objects themselves. When faced with a hat, for instance, most people sketch an archetypal side view of a hat, rather than the curves, colors and shadows that hit our retina.

In fact, artists’ special way of seeing translates into eye scan patterns that are markedly different from those of nonartists, according to a study by Vogt in Perception (Vol. 36, No. 1). In her study, she asked nine psychology students and nine art students to view a series of 16 pictures while a camera and computer monitored where their gazes fell. She found that artists’ eyes tended to scan the whole picture, including apparently empty expanses of ocean or sky, while the nonartists focused in on objects, especially people. Nonartists spent about 40 percent of the time looking at objects, while artists focused on them 20 percent of the time.

This finding suggests that while nonartists were busy turning images into concepts, artists were taking note of colors and contours, Vogt says.

While it takes years of training to learn to see the world like an artist, a common visual disability may give some people a leg up, says Bevil Conway, PhD, a neuroscience professor at Wellesley. In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2004, he and Harvard neurobiologist Margaret Stratford Livingstone, PhD, analyzed 36 Rembrandt self-portraits, and found that the artist depicted himself as wall-eyed, with one eye looking straight ahead and the other wandering outward.

This condition, called strabismus, affects 10 percent of the population and results in stereoblindness — an inability to use both eyes to construct an integrated view of the world. Stereoblind people can’t see “magic eye” images, in which a chaotic background turns into a single three-dimensional image. They also have limited depth perception and must rely on other clues, such as shadows and occlusion, to navigate the world.

Rembrandt’s stereoblindness, says Conway, may have given him an advantage in seeing the world like an artist. It’s no accident that art teachers often tell their students to close one eye before sketching a scene, he says. The eye’s imperfect optics, which form a slightly blurred image of any scene, also may be a factor, he adds.

“Rembrandt had a whole lifetime of honing the ability to render three-dimensional images in two-dimensional space,” he says.

Stereoblindness may also give lesser-known artists an advantage, Conway says. A yet-unpublished study by Conway and Livingstone finds that the art students are far more likely to have the visual disability than non-artists.

Vogt, a painter as well as a scientist, says that stereoblindness and concept-blindness help artists see the world as it really is, as a mass of shapes, colors and forms. As a result, artists can paint pictures that jar regular people out of our well-worn habits of seeing.

“As artists, our job is to get people to enjoy their vision, instead of just using it to get around,” she says.